By George Thomas, Faculty of Arts Research Events and Communications Coordinator

As 2023 draws to a close, we caught up with some of our Faculty Research Centres and Groups to learn about their highlights from the academic and calendar year, as well as activities they are particularly looking forward to in 2024. To find out more about our Faculty Research Centres and Groups and how to get involved, please see contact details and website links provided at the end of each entry.

Centre for Health, Humanities and Science:

The Centre for Health, Humanities and Science (CHHS) and its c. 200 members have been busier than ever this term and are looking forward to a number of exciting events in the new year. This academic year was inaugurated with a workshop organized by Dr Dan Degerman, a Leverhulme early-career fellow in Philosophy, on ‘Silence and Psychopathology’; this was followed by a colloquium organized by Kathryn Body, PhD student in Philosophy, on Loneliness and Shame in Health and Medicine, with speakers from the US, Hong Kong, Ireland and the UK. An event in November, co-hosted with the Wellcome-funded Epistemic Injustice in Healthcare project, brought together psychotherapists, doctors, and academics in Medicine and English Literature to talk about Trauma. The final event of the year, held in December, was an online colloquium on Modernist Literature and the Health Humanities organized by Dr Doug Battersby, a Global Marie Curie postdoctoral fellow in the English Department.

Highlights for Spring 2024 include a showcasing of Dr Victoria Bates’s UKRI-funded Future Leaders Fellowship project on Sensing Spaces of Healthcare, taking place on 14 February, followed by an early-career event on ‘Narrating Public Health Taboos’, a practice-based workshop with the artist Hannah Mumby, scheduled for 20 February. A talk on epistemic injustice by Professor Havi Carel and Dr Dan Degerman will be taking place in March. The annual Art Exhibition organized by Dr John Lee, featuring art works by students from the Intercalated BA in Medical Humanities, will be held at People’s Republic of Stokes Croft in May. On 11-12 June, the CHHS will also host a grant-writing workshop and retreat at Hawkwood College in Stroud. Last but not least, the new year will see the publication of Key Concepts in Medical Humanities (Bloomsbury Academic), a collection of essays on topics such as ‘health, ‘illness’, ‘neurodiversity’, ‘disability’, and ‘death and dying’, as well as approaches including ‘narrative medicine’, ‘graphic medicine’, ‘medicine and the visual arts’ and ‘’the Black health humanities’. The book is authored by members and affiliates of the Centre for Health, Humanities and Science.

Contact: Professor Ulrika Maude (ulrika.maude@bristol.ac.uk). You can also stay up to date through the Centre’s Twitter account.

Centre for Creative Technologies:

The Centre for Creative Technologies has had a successful year, forming a community that brings together creative practitioners, academics, and researchers. Our Alternative Technologies Workshop Series offered a great chance to reflect critically on developing technologies within the Metaverse, Blockchain, AI and Mega-engineering, and connect University of Bristol academics with Pervasive Media Studio residents.

From these connections, we saw some successful applications that blossomed into projects from our Creative Technologies Seedcorn Fund; VR games and storytelling, platform cultures, mixed reality experiences of futures in Colombia, and creative skills in animation and co-production in Amazonia. The Future Speculations Reading Group has grown, and we will be expanding the sessions with the Centre for Sociodigital Futures with a focus on community and creative technologies. The summer term ended with our keynote speaker, Dr Eduard Arriaga-Arango, sharing his research on Afrolatinx digital culture and data decolonisation. Our July event, Queer Methodologies in Creative Technologies, has developed into a two-day event in November consisting of artist workshops and an open forum; Queer Practices and Creative Technologies. The Centre curated a panel, ‘Affective Relations: Empathy, imagination and care in immersive experiences’, at the Zip-Scene conference in Prague, one of the leading international extended reality (VR/AR/MR) and interactive storytelling conferences, which was also an opportunity to network with related Centres, academics and artists in this field.

The Concept Game Jam, run with Bristol Digital Game Lab and sponsored by MyWorld, opened up conversations around Algorithmic Bias related to co-director Professor Edward King’s UKRI Project ‘Contesting Algorithmic Racism Through Digital Cultures In Brazil’. We plan to organise events to share this project’s progress, and are currently building the project page on our website with regular blogs for members to follow. Our Friday Lunchtime talk series at the Watershed will continue, as well as further collaborations with the Pervasive Media Studio. Our membership and scope have grown, and this year we hope to solidify connections between academics and PM Studio residents and develop our connection with Knowle West Media Centre by focusing on community technologies. We plan to organise a workshop series run by PhD and ECR centre members at the Pervasive Media Studio in the run up to our final summer event on community and creative technologies, with a keynote speaker.

Follow our blog to find out more, and for any queries please contact artf-cct@bristol.ac.uk.

Centre for Environmental Humanities:

2023 has been a busy year for the Centre for Environmental Humanities. Our first major event was a workshop in February on ‘the Future of the Environmental Humanities’, which brought together around 30 people from across the Faculty and beyond, together with Melina Buns from our partners at the University of Stavanger’s Greenhouse Center, and Michelle Bastian from the University of Edinburgh. This was a valuable opportunity to reflect on our existing strengths and think about strategies for the centre to develop and grow.

Thanks to the vagaries of the academic calendar, 2023 also saw two annual lectures! In June we hosted Professor Gisela Heffes from Rice University, who spoke on the aesthetics of toxicity in contemporary Latin America, and in November we welcomed Professor Imre Szeman from the University of Toronto, who discussed the future of clean energy and gave us a literary analysis of the environmental writings of Bill Gates…

Alongside these major events, we’ve been continuing with our usual programme of seminars, and have also introduced a weekly tea/coffee catch up, which has proved a valuable and relaxed space for the sharing of ideas, reading recommendations and plans. We’ve been delighted to welcome our first cohort of students on the MA in Environmental Humanities, who are already proving a lively addition to the CEH community.

We’ve begun a collaboration with a curator, Georgia Hall, on working with artists in the environmental humanities, thanks to a grant from the Faculty’s AHRC Impact Acceleration Account. We look forward to continuing this collaboration in 2024. We are also hard at work, alongside other research centres in the Faculty, on a bid for one of the AHRC’s new ‘doctoral focal awards’ on the theme of ‘arts and humanities for a healthy planet, people and place’.

To find out more about the Centre for Environmental Humanities, please contact paul.merchant@bristol.ac.uk and adrian.howkins@bristol.ac.uk. You can also stay up to date through the Centre’s Twitter account.

American Studies Research Group:

The American Studies Research Group experienced an amazing 2023! Membership increased to include over forty staff and graduate students from across the Faculties of Arts and Social Sciences and Law. Beyond our steering group, we have established three sub-committees to advance strategic goals, including partnerships, funding, and events. Our graduate training initiative, led by Dr Thomas M. Larkin and Dr Darius Wainwright, was well attended and provided important support for our PGR students. Our regular speaker series garnered positive feedback through presentations by such scholars as Ian Tyrrell, Dr Lorenzo Costaguta, Dr Erin Forbes, Dr Kate Guthrie, and Beth Wilson. We also helped to organize and host the British Association of Nineteenth-Century Americanists (BrANCA) 6th Biennial Symposium, which drew scholars from across the world to share their latest research. Our partnership with the American Museum (Bath) inspired additional consultations and collaboration, while the strengthening of our research environment contributed to new publications, including articles by Jim Hilton, Paula K. Read, Victoria Coules and Professor Michael J. Benton, and Dr Thomas M. Larkin.

Loading...

Loading...

We are excited by our plans for 2024. We will be hosting Professor Vanessa N. Gamble (The George Washington University) as the Bristol Benjamin Meaker Distinguished Visiting Professor. She will work closely with our group on funding and partnership development, as well as deliver four research presentations. We are pleased to continue hosting a range of external seminar speakers, including Nathan Cardon, Sharon Monteith, and Thomas Arnold-Foster. We are grateful for the financial support of the Faculty and the British Association for American Studies (BAAS).

To find out more about the American Studies Research Group, please contact stephen.mawdsley@bristol.ac.uk and sam.hitchmough@bristol.ac.uk.

Early Modern Studies:

The Early Modern Studies research group has had a very productive 2023. In May 2023, EMS organised the ‘Place and Space in the Early Modern World’ workshop (already reported on the Arts Matter Blog). In the summer we held our annual Summer Symposium featuring 4 panels of two speakers each, with papers ranging from early music to Anglo-Dutch identities; from stage corpses to Venus and Adonis; and from Philip Sidney’s translation of a devotional work to Shakespeare’s history plays and his will. The start of the new academic year (TB1) saw the occasion for a research celebration: many good news stories, research updates, and a celebration of two first monographs published by Dr Dana Lungu and Dr Gonzalo Velasco Berenguer. EMS will soon hold their annual ‘conversations’ event (Dec 2023); and for 2024 has further early modern events lined up.

For anyone who would like to join EMS and stay abreast of news, please write to grp-ems-internal@groups.bristol.ac.uk.

Drinking Studies Research Group:

Since its inception, the Drinking Studies Faculty Research Group has been running a research seminar series with local, national, and international speakers to bring together local members and spark productive conversations. We have had flash talks from PhD students and local academics to get to know each other better as a group, and talks from experts in the wider field of Drinking Studies. Dr Deborah Toner (University of Leicester) joined us in June to talk about her experience of collaborative work and bringing history and policy together with international partners in South America. Dr Susan Flavin (TCD) joined us in September to talk about her interdisciplinary project on early modern brewing techniques including an exciting authentic brew which was tasted by the members of the project and examined by chemists and nutritionists to investigate much discussed questions around the ABV and nutritional qualities of these early brews. In the coming year, we are hosting the Drinking Studies Network conference at Bristol (March 2024) which will bring together local, national, and international researchers to discuss writing about alcohol.

To join the Drinking Studies Faculty Research Group or propose a seminar or other activity, contact Mark Hailwood (mark.hailwood@bristol.ac.uk) and Pam Lock (pam.lock@bristol.ac.uk).

Screen Research Group:

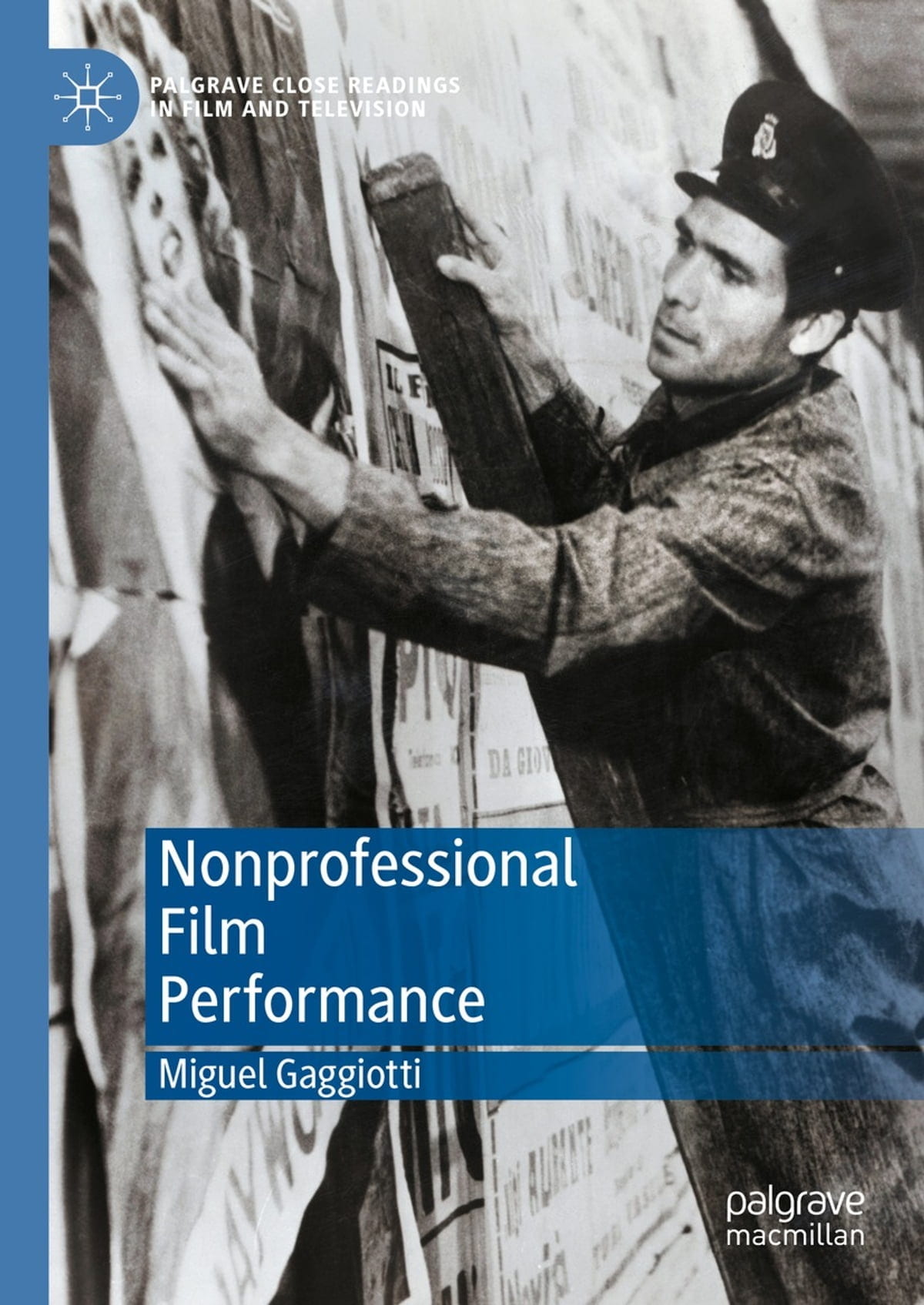

The Screen Research group had a very successful 2023. We ran a series of workshops on video-essay making, which allowed participants to develop key technical and analytical skills related to video-essay production, and to gain insight into best practices when it comes to integrating video-essays as unit assessments. The sessions were delivered by leading experts in the field, including Prof. Catherine Grant. 2023 also saw the publication of Dr Miguel Gaggiotti’s Nonprofessional Screen Performance (Palgrave Macmillan) and Professor Catherine O’Rawe’s The Nonprofessional Actor: Italian Neorealist Cinema and Beyond (Bloomsbury), two monographs greatly shaped and informed by Screen Research events, sessions and partnerships. The short films Nothing Echoes Here (Hay, 2023) and Pouring Water on Troubled Oil (Massoumi, 2023), directed by group members, also had their festival premieres in 2023. We hope to continue this success into 2024.

We will be running further events and training sessions on video-essay production, an area group members have shown a particular interest in, which has led to an ongoing series of monthly video-essay work-in-progress sessions where members share their work and receive peer feedback. The video-essay is now being adopted as a form of undergraduate assessment in the Faculty, so we are also working on best practice for assessing it, and have invited Dr. Estrella Sendra of KCL to talk to members about using the video-essay as a pedagogical tool. We will also be running a one-day practice-as-research symposium in collaboration with UWE (in June 2024) as well as a joint book launch for Catherine O’Rawe’s and Miguel Gaggiotti’s monographs in early 2024, among other activities!

To find out more about the Screen Research Group, please contact c.g.orawe@bristol.ac.uk and m.gaggiotti@bristol.ac.uk.

Bristol Digital Game Lab:

The Bristol Digital Game Lab showcased a vibrant array of events throughout 2023, providing a platform for scholars, students, and enthusiasts to delve into the multifaceted world of digital gaming.

The Lab initiated the academic year with a thought-provoking online roundtable on October 24, where experts and major UK game lab leads gathered to discuss the implications of the Video Games Research Framework (launched by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport in May) on individual research, and how game labs, centres, and networks could support its aims. The event featured two esteemed keynote speakers: Prof. Peter Etchells, who was involved in drafting the Framework, and Dr Tom Brock, the Chair of British DiGRA.

Following this, on October 31, the Lab collaborated with Digital Scholarship @Oxford and organised a hybrid panel and roundtable titled “Music and Sound in Games”. Expert speakers from both industry and academia dissected the impact of music on gaming narratives, characters, and emotional engagement. The digital roundtable facilitated by Dr Richard Cole further delved into critical conversations surrounding this fascinating aspect of game design.

November brought a Research Seminar in collaboration with the Department of Classics and Ancient History. Dr Dunstan Lowe, Senior Lecturer in Latin Literature at the University of Kent, presented on “History is not the Past”: Videogame Design and The Ancient Mediterranean. The seminar explored how video games portray ancient history, emphasising the diverse ways in which different genres and playstyles influence the conceptualisation of ancient worlds within digital games.

Towards the end of November, the Lab hosted an exciting inaugural event, the ‘Concept’ Game Jam, co-organised with the Centre for Creative Technologies and sponsored by MyWorld. The Game Jam challenged the 40 participants to explore how gaming mechanisms could shed light on the biases embedded in algorithms, especially in the realm of machine learning and AI. It stimulated creative thinking about the intersection of gaming and algorithmic bias and some teams came up with innovative working prototypes.

December will start with the Antiquity Games Night, a novel monthly online meetup organised by Dr Richard Cole and Alexander Vandewalle (University of Antwerp/Ghent University). Scholars, students, and designers will gather to play antiquity games, fostering an engaging space that blends academic discussions with gaming experiences.

Closing the year on a festive note, the Lab will bring back the “Festive Gaming” event on December 14. This event will invite participants to join in for an evening of social gaming, featuring the latest releases and playtests of upcoming games. The lineup included contributions from Catastrophic Overload, Meaning Machine, and Auroch Digital, providing a platform for networking, exploration, and celebration within the gaming community.

In summary, the Bristol Digital Game Lab’s 2023 events were a testament to the diversity and richness of the digital gaming landscape. From scholarly discussions on research frameworks and ancient history to hands-on game jams and festive gaming, the Lab succeeded in creating a dynamic space that catered to a broad spectrum of interests within the gaming community. The Lab has expanded to a network with more than 150 members, gaining increasing recognition internationally.

Looking ahead to 2024, we will be hosting an ECR/Postgraduate work-in-progress event in January, followed by a series of industry talks with a headline from Ndemic Creations, a roundtable on accessibility, as well as a conference on New Directions in Classics, Gaming, and Extended Reality. We look forward to seeing you there!

To find out more about the Bristol Digital Game Lab and sign up to our mailing list, please visit: https://bristoldigitalgamelab.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/how-to-get-involved/.