With the Bristol Harbour Festival 2022 not long behind us, we caught up with Dr Nick Nourse, Honorary Research Associate in the Department of History, to learn more about sea shanties – their relevance, their history, and their intricacies. A trained violin maker, Nick went on to study for a musicology MA and PhD at the University of Bristol. His PhD thesis ‘The Transformation of the Music of the British Poor, 1789-1864’ focused on his research interest in the low ‘Other’ in society, in particular their musical tastes and their roles as listener, consumer and performer of popular entertainment. As part of this research, Nick studied the musical history of sea songs, and he shares some of that knowledge with us now:

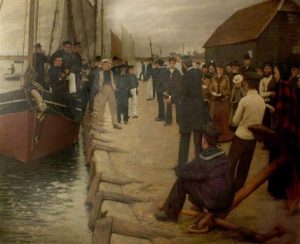

In January 2021, the Bristol band The Longest Johns were signed by Decca Records after their version of a nineteenth-century sea song, ‘Soon May the Wellerman Come’, went viral on TikTok. During the restrictive measures of various Covid lockdowns, The Longest Johns also became one part of an online craze under the heading of shanty-singing. With the return this summer of the Bristol Harbour Festival and a Bristol Sea Shanty festival arranged for September, now would be an ideal point to explore the history of this unique sea song.

In brief, the sea shanty was a work song sung on board merchant sailing ships. Its purpose was to synchronise the crewmen’s effort when engaged in heavy and monotonous physical tasks, such as hauling on a rope or tramping around the capstan to raise the anchor.

Stan Hugill, the acknowledged expert on the subject, divides shanties into two primary groups: hauling, and heaving songs. Broadly speaking, he places regular-paced and continuous heaving work at the capstan or bilge pumps as being to poorly disguised marching songs in 4/4; the hauling songs were for stop-start strenuous work often to a 6/8 metre and less musical. The hauling shanties in particular follow the call-and-response form, in shanty-dialect called ‘order-and-response’.

Take, for example, the shanty ‘Blow the Man Down’. This is a Halyard Shanty, a song sung while raising or lowering the sails (in full sailor parlance, this is halyard hauling: halyard = haul + yard). The work could be extremely heavy, and a halyard shanty therefore was sung with the crewmen taking a rest during the leader’s call and only pulling on stressed words of the chorus. Sung in 3/8 time, the shanty often starts:

Solo: ‘As I was a-walkin’, down Paradise Street’

Crew: ‘To me Way, hay, Blow the man down’

Solo: ‘A sassy young clipper, I chanced for to meet’

Crew: ‘Oh, Give me some time, to Blow the man down’

Given how long it took to raise a large sail, for instance, sea shanties could be 20 or 30 verses in length, and it did not matter what order they were sung in. The main aim was rhythm, but also distraction, to take the mind off the boredom of the physical task. To that end, songs could be re-written on the spur of the moment, so Paradise Street could become a well-known street in the ship’s last port of call. And like folk songs, the words often held more than one meaning: the ‘sassy young clipper’ is not a reference to a ship, but to a woman.

One particular function the shanty could achieve was to voice complaint about the captain or another crewman: singing out their grievance was often the only way for a sailor to voice his anger without being disciplined.

The sailor’s sea song is subject to much superstition. The shanty, for example, was only ever sung on board ship, never on shore, always to work, and never off-duty or for entertainment. Likewise, anchor-hauling songs were split into outward- and homeward-bound songs, and they should never be sung on the wrong leg of the voyage.

The origins of the sea shanty are unclear, but its heyday was in the early- and mid-nineteenth century and followed the end of hostilities between the French and the English. Peace saw the resumption of world sea trade and travel, trade which was encouraged by the gold rushes of North America and Australia. The term itself comes in multiple spellings: shantey, chanty, or chantey — all pronounced as if with a ‘sh’ — plus various grammatically dubious plurals. The Oxford English Dictionary date ‘shanty’ to 1869, but Nordhoff’s The Merchant Vessel, first published in 1855, writes of ‘The foreman is the chantey-man, who sings the song, the gang only joining in the chorus, which comes in at the end of every line’.

Musically, Hugill suggests the sea shanty as having its origins in the folk songs of England, Ireland, Scandinavia, Germany, and colonised North America – including Canada and Newfoundland – and in the slave plantations of the southern states of America.

To return to The Longest Johns and ‘Soon May the Wellerman Come’, this is not a working song, but a fore-bitter. In contrast to the shanty, the fore-bitter was sung off-duty and for entertainment, but still as a distraction. It gets its name from the fore-bits, large wooden rigging posts in the foc’sle (forecastle), and the place where sailors would gather in good weather to relax and kill time. The subject and sentiment of either form of song was tremendously wide, from love — both true and sentimental — to loss, often of home, from complaint to celebration, and from wealth to glory.

The sea shanty today holds its place alongside traditional, or folk, song as a recovered and preserved work song. As steam replaced sail in the second half of the nineteenth century, the need for collective physical duties on board ship declined, and with it, the sea shanty.

Dr Nick Nourse, Honorary Research Associate, Department of History